To Whom it May Concern by Plangdi Neple

"They were born dead, spirit hovering over their lifeless pudgy forms." | Short Story #1

Hello fellow strange pilgrims, today’s short story—when I first read it—made me want to scream-dance. I don’t know what that is, really, but that’s how I felt. The way Plangdi Neple weaves between the second-person “you” sections and Plangnan’s story creates an incredible tension—we’re simultaneously watching the instruction manual and the origin myth, and they illuminate each other in divinely perfect ways.

ABOUT THE VOICE ARTIST: Abdulsalam Joki-Lasisi is a Nigerian engineer and professional Voice Over Artist. From lending authority to multinational brands to breathing life into diverse animation projects, his vocal range is matched only by his passions for gaming, reading, and sports.

Raise a plastic fan and hold it next to your head. Turn it slowly, your head facing forward, until you start to hear sounds. The sounds change every night; running water, TV static, a stampede, whispers, a festival, but never turn your head to look. With your other hand, reach across your face and feel the air around the fan, closest to where you think the sound is coming from. Feel, until something licks you.

That is when you know you have found Them.

There are many stories about how She came to be. Some say She was born when lightning struck a boulder at the base of Shere hills. Aunties tell their nephew that She was a babalawo’s illegitimate child, created by the gods to punish him for his infidelity. All versions are useful, have power.

There is one story that isn’t shared as much. I wonder why. But, you’ll need this version to be able to get her to do what you want.

The story goes thus:

They were born dead, spirit hovering over their lifeless pudgy forms. They were born in a tub, in a bathroom with high clay walls and a flimsy zinc door. They slid out of their mother, a soul with a tightly curled body. She didn’t scream, this mother. She rinsed the body, that silent breathless baby, then washed herself. They watched, curious.

Her lips tight, their mother dug out a spool of thread and a needle attached. Their curiosity morphed into horror and they tried to scream. But spirits cannot scream to the living, so, they could do nothing but watch, dread curling, as the mother pricked her finger, then stabbed the dead baby’s stomach. and blood began to flow along the thread, white to red as it flowed into the body.

Then the body’s eyes opened, and it began to cry. The mother cried too, and hugged the body. The body looked at where They floated, close to the yellow bulb, hatred clear in their eyes. And it smiled. Through its tears, it smiled, and curled further into the mother.

“Thank you God,” the woman cried out, voice hoarse from hours of unaided labour.

Like a summoning, the zinc door flew open with a grating squeal and a man barged in. He nearly tripped over his hastily tied wrapper, almost bashing his head against the enamel tub. And They winced, annoyed at Their failure. He re-tied the wrapper hastily and loomed over the wife, smiling a smile that chilled Their bones.

“It’s a girl,” the mother whispered. And handed the body to her husband. The body that now lay so still, it was like watching a statue passing hands.

“Yes,” he said, his lips curling. “Yes it is.”

When you find Them, when they have licked your hand, draw it back. If you don’t, their teeth will follow. It is not time for the teeth yet.

You will feel afraid. Your heart will pound and nervous laughter will tickle your throat. Laugh and be nervous, sweat even, as you make dinner and think about what you want to do. What you want them to do for you.

But when you hear the gates swing open, when you hear Musa’s welcome sa! good evening sa!, compose yourself. Smooth your hand over your headtie as you walk to open the door. Hug your husband and inhale his Dior Sauvage like you have missed his scent all day, and cannot wait to have him all to yourself.

“Ah ah, is that how much you missed me?” he will ask.

Smile and say yes.

As you close the door, your eyes will find it. A red thong, leftover from your afternoon dalliance with Fatima.

Look quickly, to see if he saw, then swipe it with your toe, nimble as a gymnast. You might make a noise.

“Did you say something?” he will turn and ask.

Shake your head no. He will frown, like he doesn’t believe you, and your heart will start to pound. But don’t panic.

Pout your lips and graze his arm with your newly manicured nails. It doesn’t matter that you feel nothing, like touching a tap. Do it till his pupils dilate, and his breathing changes. Then leave him and go back to making dinner.

It always used to work on Rhoda, and it will work on him too.

That night, after he has fucked you (never the other way around), tell him you want to shave his beard. His smile will be confused, but rub his chest. Feed his vanity; make him think your fingers’ only purpose is to be glued to his body.

As you lather his chin, leave a small patch without shaving foam.

Shave the rest, carefully, stroking his face so his eyes flutter and he has a constant placid smile.

“Let me use my tweezers.”

Pluck the hairs, dark and short with their whitish root/follicle, and place them inside a square of tissue. Your heart will race, and your fingers will tremble, but force yourself to relax.

Later, when his snores make the windows rattle, and makes you want to slap him, grab your fan again. Reach for them, to the place where They are. This time, when you reach across your face around the fan, give them the tissue-wrapped hairs. Their teeth will graze your fingers, and latch onto the hairs, and a wet, cosre tongue will tickle your fingertips. Then they will disappear.

Seven days later, they will give you several pouches of powder, and you will poison your husband for the first time that night, watching with satisfaction as he swallows each morsel of pounded yam and laced afang soup.

Every time the mother had gotten pregnant, she’d had a miscarriage. That is what They are made up of, the spirit of each baby she miscarried. Each tragedy was an omen from the Old spirits, a warning that she should not have her husband’s baby.

You see, the mother and her husband had gotten married despite her parents’ pleas. They’d even locked her up in her room, threatening to sell her to the highest bidder should she accept the man’s proposal.

Everyone in the village knew who he was. They kept their daughters behind them as they danced forward every Sunday to drop their offering, or to receive anointing from his Goya olive oil bottle. No wife ever went to see him without her son or husband, and spiritual deliverances were always a family affair.

But the mother…the mother was different. She would go to see him alone, and each time returned to her parents’ house with a pious fire in her eyes, singing hymns and dancing tilll 3am when the neighbours would band their windows and say, “will you shut up!”

Her parents tried to talk to her. But they did so in discreet terms, words that made little sense to her, to anyone who would need protecting.

“Plangnan…haven’t you heard…he’s not…”

But the girl didn’t understand. He was kind to her, spoke in a soft voice and stroked the back of her knee every time she went to see him. He was handsome, skin like clay, and brown eyes that sparkled when he lit his kerosene lantern at night. And he was the first man whose touched moved her, made her skin prickle and her nipples pebble. A person that wasn’t a girl, that wasn’t her “best friends” over the years.

So, she believed then, that he must have some ungodly power, since no man had every drawn moans from her the way Shitna’an and Miriam and Blessing did.

She had gone to him for deliverance, for counselling, when she heard his first sermon condemning homosexuals, and she felt something ugly choke her chest. It was the same feeling that suffocated her when at 19, whispers began to follow her. At the river side, in the marketplace, in the village hall.

“Did you hear?” “Hear ke? I saw them with my own eyes! Her and that Deborah.” “Tufiakwa. And you did not kill them??” “What’s my business?” “Let me catch her first. If I don’t chop her up, change my name.”

She hated the words, hated the fear that took root in her, that fed on her apparently ungodly desires. So, of course, she’d gone to the pastor for help.

“You see,” he whispered as he stuck a finger inside her and she writhed, clutching her breasts. “How can you be gay?”

She married him, and the whispers stopped. No one ever whispered against a pastor and his wife.

Until she miscarried four times in a row, and the whispers arose again, triumphant, vindicated.

“When she has been doing rubbish with that other girl for years, what do you expect? I’m sure that’s why God closed her womb. Useless girl.”

She would lock herself in her wardrobe, and cry till her husband came home to berate her over semo and kuka about her childlessness five years into marriage.

They did not know that it was the spirits handiwork. Spirits pay attention, they see the future, written in the actions of the past and present. They knew what would happen should the man have a child.

Then one day, she took matters into her own hands, and fucked another man where eyes could not see, where whispers could not be birthed, and even spirits were oblivious.

And gave birth to her daughter, the girl who would be her downfall.

Your problem, your husband, will be like an overnight pimple. Irritating, disfiguring, and you will want to pop him as fast as possible.

Bide your time. Every day, you will want to increase the dose. Don’t. Be like Beatrice Achike, like Giulia Tofania. They were careful, and no one found out till it was too late, till their problems were dealt with.

He will invite his friends over for his 40th birthday celebration, and they will drink all the booze in the house, till you have to send Musa to buy palm wine from around the corner.

“Please be fast,” you will say. Because you do not want them, him, to be sober.

You do not want him to be able to understand the looks that pass between you and Miriam, Bello’s wife.

The first time you met him, at your introduction, he’d seen the look.

You saw a look too, one that made you roll your eyes. As you walked past him from the front door to change out of your clubbing clothes, you took in his big-bellied figure. Greed, potent and oily, shone in his eyes and in the way he stroked his beard. He was nothing new. The newest in a long line of men who’d visited the house over the past two months, you thought you could dispose of him too, prove to be so hard-headed they would leave.

No matter how much money they stood to inherit from your oil tycoon of a father, no man wanted a headstrong wife that they couldn’t control.

So, when your mother called you from your room, you mad sure to emerge in only a towel, tattoos on full display.

“Sochi,” your mother said. “Come and meet Isaac.”

“No,” you said loudly, and the room fell into silence. Your mother’s mouth fell open and she rose, the beads on her arms and neck rattling. She raised her hand to slap you, and you flinched, closing your eyes. Nothing came.

You opened your eyes to find her wrist stayed by the man. The way he looked at you then was different from the other men. Pitying, triumphant, possessive. Your knees trembled and you bit your tongue. Real fear crippled your nerves and you fiddled with the edge of your towel.

“Let me talk to her alone please,” he said. Everyone agreed. Your mother, father, uncles, all filed into the kitchen, and silence descended between the two of you.

He said nothing, simply pulled out his phone and scrolled and tapped a few times, then handed it to you.

You threw the phone across the room. It burned your hand, and the picture collage on it was scorched into your retina, and angry tears welled up.

“How the hell did you get that?” you whispered.

It’s fine babe, Rhonda had said. No one will know. Yet, there the two of you were imprisoned on his phone, lips locked and hair tangled in one another’s hair, chest smooshed together. In another picture was one thathad you both staring at each other’s eyes, two girls clearly in love and damning the world.

Isaac smiled, and his oily wretched face turned triumphant in your sight.

“Marry me,” he’d said. “Marry me or I’ll tell everyone what a dirty lesbian you are.”

The skin on your arms pimpled and you hated him instantly.

“Tell them,” you said. The smugness slid off his face and for the first time, he looked unsure. You smiled, your confidence returning in bits, masking the fear that thrummed in your veins. Then he marched past you into the kitchen.

He told them, and the next week, you were married.

Two years now, and you still hate him, want him to suffer for the life he has trapped you in, a life created out of fear for your own life.

But he doesn’t know that your boldness has gone nowhere, despite the gold handcuff on your ring finger. You are still that girl in the towel, her tattoos now covered by bulbous bubus. It is that same boldness that led you to find a witch, one who didn’t fear your husband, who had his own army of babalawos, thanks to your father’s money.

“I can’t help you,” she’d said. “I will die. But I know who can help you, someone your husband cannot touch, because she is already dead.”

Thanks to her instructions, now you have the poison, and soon, you will be free. Maybe not to go back to Rhonda, who is married with two children now. But to live a life where you do not have to think of someone else when being fucked.

When Musa returns, Isaac’s eyes will be a little less glazed.

“What took you so long?” you will snap at Musa.

“Sorry ma,” he will reply. “E don finish before, but dem make new batch special for oga.”

As you transfer the palm wine to a jug, Miriam will join you in the kitchen.

“Let me help you,” she will say. Her voice is soft, and has always done something to your belly. This time, for the first time, her fingers will graze yours as she lines up glasses on a tray. They will linger, as will your eyes on her fair face, breasts hugged by sugar lace, and a mouth ringed in kohl. Then she will drift past you to the stairs, up to where she knows your bedroom is, where you have gossiped about your husbands. And their many girls. And whispered, coded desires. As she walks up, one shoulder of her dress will fall. There will be no bra strap. You breath will stutter and your eyes will remain on her till she disappears past the landing.

All that’s left is to deliver the palm wine, then join her.

You pause, then pour an entire pouch of powder into the jug. Because they are the same, the men drinking and laughing in the sitting room.

No one she told believed Her. Her grandmother had slapped her and said to stop dreaming up stories.

“You want the devil to use you abi?” she said.

Her mother hadn’t said anything, simply stared at Her till she began to doubt what had happened. Maybe I am exaggerating, she thought. No father would touch his daughter that way, the same daughter he fed strawberries at breakfast and made faces till she collapsed into breathless giggles.

You see, one day, Plangnan had come home early from church choir practice. That particular day, she was not interested in being fetted, fawned over and asked to deliver prayer points to her husband. She packed her bag and faked a headache, and left. Somehow she still ended up with two written prayer requests.

On getting home, she fished out her key from her purse, when a soft, whimpering sound made her pause. She stepped to her left and squinted to look into the window, wondering if there were thieves raiding their home so early in the evening.

What she saw stopped her heart forever.

On the couch lay her daughter, clad in her nightdress. Kneeling in front of her was the pastor, his hands beneath the nightdress, a smile on his oily lips.

Plangnan retched. Outside the door, she emptied her stomach of everything ever ingested. The lies, the faith, the sermons, the belief. Then she sat in the putrid mess and prayed, prayed she had mis-seen, because no father would do that to his own daughter.

She replayed her counselling sessions with him, how he’d fingered her. This time, she paid attention to the look in his eyes, not how her body felt, a body that now felt like a betrayal, a supreme lie. And for the first time, she saw it. The look. Punishing, triumphant, wicked.

She kicked the door, feet stinging, and swept on them. Her bag became a gavel, metting out justice onto her husband’s back. He cursed and tried to overpower her, lifting his hands. As soon as he did, she whacked his face with her shoe and scooped up her daughter and ran, locking them both in her room. Her daughter shook in her arms, tears glinting in the wam yellow light of the overhead bulbs.

“Plangnan!” he roared and pounded on the door. All night he threathened and shouted, voice going hoarse. Till he finally left, and her daughter slept, and Plangnan’s heart still did not resume its natural ryhthm

Naturally, she’d gone to her family for help, for solace and protection, the same people whose warnings had falling on her deaf ears, the same people now ho dismissed her.

How could a father do something like that?

Soon, stories of her accusation began to spread. People stared as she and her daughter picked out pawpaw and cashews in the market. Their eyes tracked her daughter’s movements, looking for the pastor’s fingerprints on her skin. And when they didn’t see any, when she looked normal, eyes burned with anger, lips curled, hissing. Plangnan hurled a few cashews, toppled a few pepper heaps.

Normal to them was not normal to her. She knew from how her daughter didn’t complain about buying overipe mangos, how she didn’t beg for boiled groundnut, how she pulled Plangnan away from every male trader, that her daughter’s scars lay in her bones, swam in her blood.

And she knew those scars demanded retribution.

She went home and performed for her husband. She pouted her lips, grazed his arm, caressed his shoulders as she served him dinner. She laughed as he joked, made he saw the heat in her eyes, made sure he mistook it for smoldering. Her daughter’s sadness and betrayed expression at the dining table clawed at her chest and almost broke her resolve.

That night, after he fucked her (never the other way around), and he dozed off, his stomach full of pounded yam and egusi, Plangnan steeled herself, took a knife, and plunged it into his fat kneck, where his rosary rested. And blood coated the cross, gargling till his struggles fell silent.

They saw, the spirits of the children that died in her womb. They saw what this woman had done in the face of what they had foreseen, the injustice that would have been committed against them too. And They smiled.

She went to wash her hands of his blood, and They descended, possessing the man’s body. He rose from the bed, a quiet zombie, blood leaking from his throat onto his night shirt. He walked out into the night, guided by Them under the watchful moonlight.

When Plangnan returned to the room, she screamed. Then she turned the whole house upside down, movenents frantic and deperate. She ran outside, searched the nearby bushes for him tilll the sun rose and her eyes were blood-red.

For days, she could not sleep. She waited for his resurgence, his resurrection and her subsequent damnation. For what dead man stood up and walked away ?

But weeks passed, and he didn’t return, and her confidence grew, even as people whispered about his disappearance.

The next time they were in the marketplace, the people stared, once more looking for the truth. And they thought they saw it, in the lightness of her daughter’s footsteps, the way she walked with her shoulder’s high like a layer of slime had sloughed off her. They thought her, the re-happy 5-year-old, responsible for her father’s disappearance.

Plangnan felt the fiery hate in their eyes, the pitchforks and torches that would come for her daughter if they believed her guilty. The fear tore at her throat, and her heart became irregular.

That evening, she called Deborah, who now lived in the city, a successful banker.

“Hello?” the voice pulled at something deep and long-forgotten in Plangnan and she had to stifle a sob.

“Deborah? It’s Plangnan.”

“Plangnan! Long time! How-”

“I’m going to die soon,” she interrupted. “And I want you to come and take my daughter away.”

Deborah was silent, shocked. “Why?”

Tears ran down Plangnan’s face. “You know what this village is like.”

She didn’t need to say more. Deborah agreed, and they scheduled the pickup for two days later.

That night, she went to Mama Iyabo’s beer parlour. She sat for hours, ordering cup after cup of burkutu. She poured them all over her dress when no one watched, so by the tme the moon graced the sky, she smelled like Katlong, the town drunkard. Then, heart thumping, she climbed onto the table. She took a deep breath. Then began to scream.

“I did it! I killed him! I killed the useless man.”

Jumping from table to table, kicking cups and plates, sending meat and booze flying. For the first time since she was a girl, joy filled her heart. She was no longer a dirty hell-bound homosexual, a stubborn girl, a barren wife, a lying wife and mother. She was a mother, fighting for her daughter, taking her protection into her hands.

It didn’t take long before people captured her, tied her up at the tree at the base of the mountain. And they stoned, hurled and threw until her body bled in all places. Her wrapper and clouse tore to shreds. But she laughed. Laughed because she knew her daughter would be safe.

As the life flowed out of her, and her connection to this side of life ebbed, she saw Them, and They reached out hands to her.

“Who are you?” she asked, voice cracked. Another stone hit her temple and destroyed her left vision.

“We were to be your children by that man,” They replied. “Join us, mother.”

Plangnan smiled, and the last stone hit, and she joined her children.

It will look like you will fail.

One day, he will come home to find you dozed off on the couch, phone hanging from your hand. He will take it and his body will go rigid. Fury will twist his dark face, till he looks like a pudgy potato.

The first blow will clear your sleep, and feel like nails driving into your cheek. The next will fold your stomach in on itself. He will grab your hair and pull you from the couch. Pain will explode at the base of your skull and tears will run down your cheek.

You will swipe helplessly at him, but pain has weakened your body, and the only thing you can do is scream and sob.

“I thought I told you to stop this nonsense!”

They will come to mind, Fatima’s red thong, Miriam’s lace-covered breasts, the countless women that have kept you sane, stopped you from taking your own life just to escape this prison.

He will do all these things, and your patience will break. This is where They will come in. They will come from the shadows and enter his body, replace his soul. He will jerk and try to fight. Then his fingers will unclench from your head, step back and watch.

He will tear himself apart, from hair follicle, to fingernail to skin flaps, till he is nothing but a mess of bone, suit scraps and blood.

Sometimes, there is no such thing as a clean ending.

Fear will try to overtake your body, will freeze you to the spot. Take your bags and run. Run towards your new beginning, one that starts with a plastic surgeon who will replace your face with an unrecognisable one, bland and mundane.

When they find his body, see what has happened, the insects living in his skin, they will call you witch. But not to your face, because it doesn’t exist anymore.

Witch, they will call you. Witch, they called women miracle workers. Divine, they called Jesus. Does it really matter? Witch, devil, they called Plangnan. She is the She they tell stories about, the witch they use for horror stories. Maybe they’ll use you for a story too.

And sometimes, for the sake of those who come after, our stories are more important than what they call us.

Tell us your origin story as a writer. When did you begin? What first drew you to writing as an instrument for asking questions that can’t be explored any other way?

Plangdi Neple: Until 2020, I didn't consider writing as a thing I could do professionally. By then, Covid-19 had made me bored enough to try anything. Plus, I was unhappy with my chosen field of study: Chemical Engineering.

My real draw to writing came about 2 years later, when I was considering stopping for good. Until I found what I really wanted to do with words. I don't talk much, so, writing (and the accompanying research) is my preferred way of asking questions I can't say out loud, and for talking about important things.

What does your writing routine look like? Do you thrive in structure or wildness? And when you begin a piece of writing, what tends to announce itself first: a voice, an image, an unease, a philosophical conundrum?

PN: 90% of the time, structure. Wildness can occasionally help and surprise (that's actually how “To Whom It May Concern” started out), but has more often led to incomplete drafts that taunt me every year. Structure helps because I need to have a clear road map. If not, I'll retread old/familiar themes and stories.

The thing that comes first is usually a question: what if...? Followed by a twist on something I've been preoccupied with. For example, I have a story that started as "what if I wanted to steal money on its way to an ATM?".

Most artists are preoccupied by certain obsessions: lust, longing, death, the self. What persistent preoccupation—emotional, intellectual, or spiritual—threads through your work? Are there motifs, themes, or impulses you’ve tried to abandon but that keep returning, insisting on their relevance?

PN: Oh my friends would have a field day answering this! The most consistent thing in my work (right now) is queerness. It wasn't always there when I was growing up, especially in Nigeria, and writing has given me the power to surround myself with it. Another thing is that a lot of my characters go to others for help/power. A part of it is that I think it's important to know when to ask for help (something I'm not very good at), and to understand the need for community.

If not a writer, who would you be?

PN: Probably an engineer, if my parents had their way!

What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received? Alternatively/additionally, what’s something you’d like to offer as advice to emerging writers trying to make a mark?

PN: The best advice I've received is from a friend: do it afraid. And it's the same thing I'd say to emerging writers. You already have so many things working against you in the world right now. Don't let fear be one of them.

What are you working on now and how is it trying to ruin your life (in a good, necessary way, of course)?

PN: I'm afraid I'll invoke them if I speak. Oh well, what's a little curse. I'm working on a novel and a short story collection. One is about beauty, fashion, and the body, and one is about gender essentialism, surveillance states, and addiction. I'll give you 3 guesses.

Who are the artists—writers, filmmakers, thinkers, internet oddities—that have shaped your sense of narrative? How have they rearranged the way you see the world on the page?

PN: There are so many people I can think of, but I'll stick to a few. Tee Noir, Cat Sebastian, Mina Le, Octavia Butler, Wole Talabi. I didn't really grow up questioning the world around me; I grew up Christian. These writers and creators gave me the language to express things I already felt, and exposed me to history and concepts I was otherwise oblivious to. They're also just really fun! Wole has a story (An Arc of Electric Skin) about a man using his skin to destroy the Nigerian political system. Delicious doesn't begin to describe that narrative.

Please recommend a piece of art (a painting, a film, an album, anything that's not a piece of creative writing, really) that you love and would like everyone to experience.

PN: Two very recent things come to mind: Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio Maison Margiela Artisanal 2024 show.

PLANGDI NEPLE is a Nigerian writer. His work has appeared in several publications, including FIYAH, Cast of Wonders, Flame Tree Press, Afterlives 2024: The Year’s Best Death Fiction, and others. He is a Voodoonauts 2024 Fellow, a Tin House Alum, a member of the Clarion West class of 2025, a Nommo Award Nominee, and a Brave New Weird Award winner.

Notes on Art

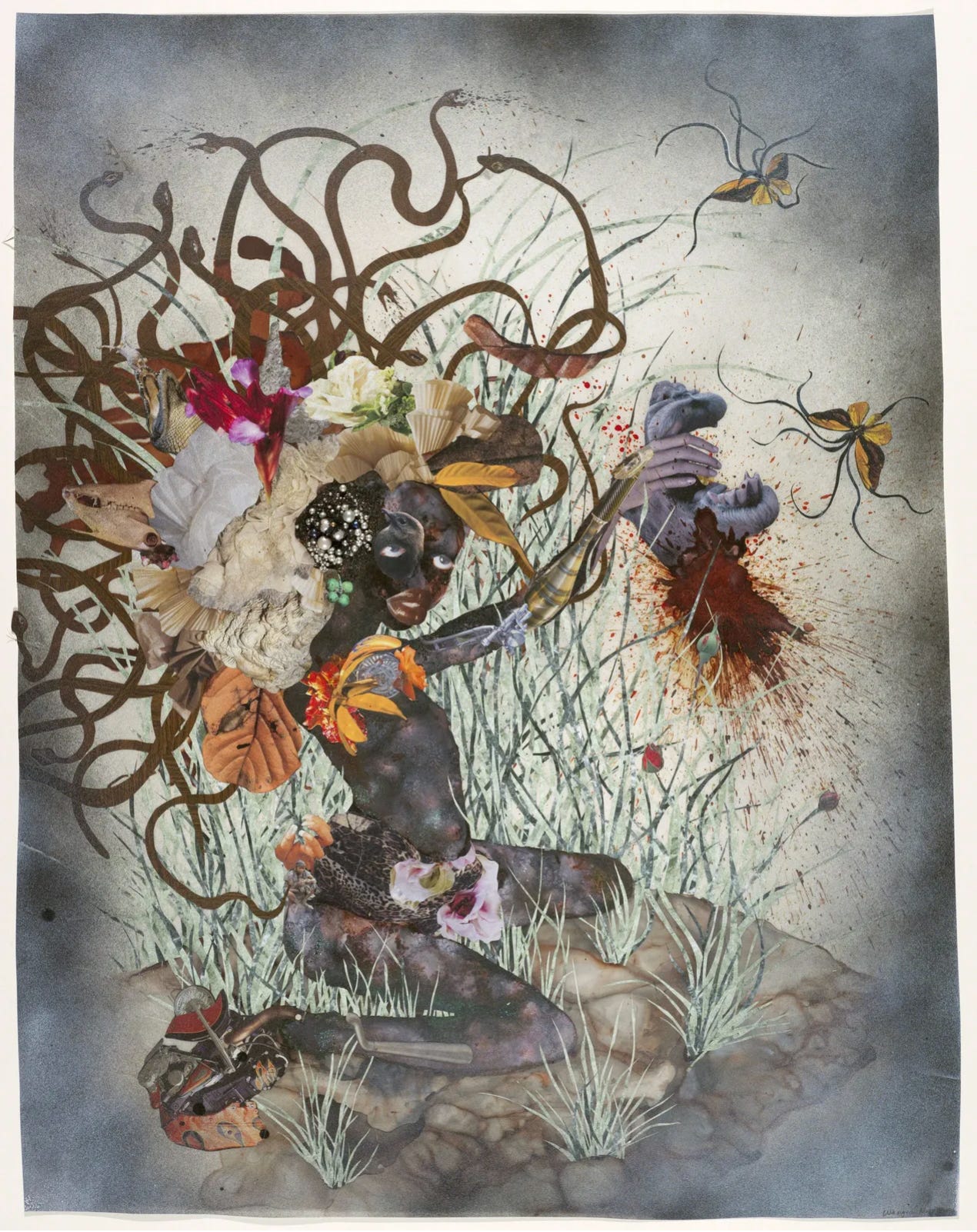

We’ve paired this piece with Wangechi Mutu’s The Bride Who Married a Camel’s Head (2009)1 Mutu builds hybrid women from magazine cutouts, medical illustrations, and ink—figures torn apart and reassembled into something fiercer. This bride kneels in tall grass, flowers erupting from her head like a crown or a wound, one hand raised as if casting or catching something. She’s ornamented and monstrous, trapped in a title that sounds like a folktale warning and a curse. And then we look at her face and realize, viscerally, that she’s not afraid. Neple’s story takes off from that look.

Image: The Bride Who Married a Camel’s Head © Wangechi Mutu. Used for editorial commentary purposes only. All rights reserved.

Beautiful work! Case in point to the author's noted interest in gender essentialism, I assumed throughout I was reading a woman author, since the character's perspective felt so realized. Thanks for publishing/sharing.

Very cool to see you’ve been shaped by Octavia Butler. The balancing of the thoughtful themes and the horror reminded me of her work.