Brief, Generalized Tremors by C.R. Calabria

"What if I told you I never did it for the money." | Essay #1

Hello fellow strange pilgrims, today we present you an essay that holds a mix of the clinical and the devotional, turning medical procedure into an act of revelation. I feel it’s quite rare to encounter writing that’s both this precise and yet so unguarded.

ECG SCAN # 1

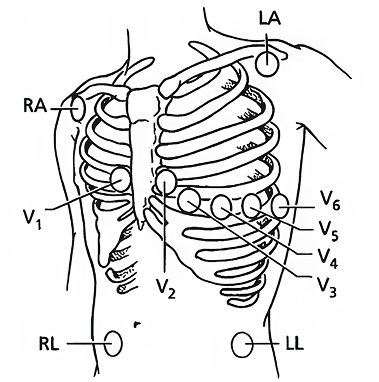

What if I told you I never did it for the money. That, lying here, shirt off, nipples hardened in the cold lab room, my skin warmed with anticipation against the cool leather of the blue medical bed, like Amélie at the approach of her father’s stethoscope, I thought of boiling eggs: how the trick to a good peel is to shock a cold egg with high heat until the proteins beneath the shell form into a gelatinous ball. What if I told you that the 12-Lead electrocardiogram has only ten electrodes, connected to the body through sticky pads. And when the nurse places them on my warm skin: A rush. Often, creatures react in the exact same way, like my friend Zach’s corgi when I grab his toy off the ground. A sharp turn of the head. Saliva forming at his lips. Toy morphs into anticipation; becomes something else yet. The electrodes click onto the pads, and it’s like the peel after boiling. The egg is halved with anticipation, the outcome always unknown, which makes the reaction known, regular. My heart slows down, speeds up, skips a beat.

The placement of the chest pads is precise. There is always an adjustment. A stranger’s hands press into my chest, feeling for something. Pulse? I think, unsure what else, if anything, one might find there. The medical term is precordial. There’s so much I don’t know. The key is V: V1. V2. V3—V6. The auxiliary pads, the ones on the arms and legs, read the heart from six points of reference. Left leg (LL), right arm (RA), left arm (LA). The machine calculates: left leg plus right arm, left arm plus right arm. Right leg (RL) grounds the currents, creates a pathway for patient and machine.

I am a vector of electricity. A rush takes the blood from my cheeks. The machine calculates: right arm and (left arm + left leg), halved. Each pad is a vector of electricity. The button is pressed, the machine hums, whirs, the pink graph paper populates with peaks and valleys. I wait for the prognosis and the rush floods me, the egg cracks, and the machine promises, leading me toward what I know it cannot: wherever is beyond doubt.

APRIL 2024

Seated in the waiting room, the Informed Consent sheet on my lap, it dawned on me that I’d forgotten to read about the study before traveling two thousand miles, for if I had, I never in my wildest dreams would have come so far.

Mercury was in retrograde, and so I expected the worst, and found it. The price of my flight was inflated, and went down to a normal price only after I bought it; my connecting flight was on alert due to an adverse weather event, but customer service wouldn’t let me change it because the flight hadn’t been canceled yet; the adverse event never came, but the A/C went out in the cockpit of the connecting flight, leading to a five-hour delay and three gate changes; and the motel I booked sent me a message saying my booking could not be completed, so I wasn’t sure when I eventually arrived, around 1 a.m., where, exactly, I would sleep.

It was the era of the protein study. This one was developed as a potential treatment for Phenylketonuria, a rare, inherited disorder that inhibited the body from processing protein. The side effects page was short and theoretical; educated guesses from the studies done on animals. The first one that caught my eye warned of a potential for a “change” in the heart muscle. Paired with weakness and muscle pain, it was clearly meant to signal a bad that was either so severe or unknown as to be rendered generic.

Phase I, which was the first time a human took an investigational drug, was also called first-in-human, meaning that animal trials had been conducted, and results were promising enough to continue. It was sort-of required to report these findings in the Informed Consent, but the range was high, making it feel like sponsors could put in whatever they wanted. Rarely was there too much information, and more often there was little to go off of. This Informed Consent was detail-heavy, providing several “highlights” from the animal studies, but none of them were delivered with enough context. The result was a medical document that bordered on absurd, a medical exam set in Wonderland.

For example, even though the Informed Consent listed rats, monkeys, and dogs as “pre-clinical” subjects, it was—curiously—only the dogs that made the page. But the form said nothing about how many dogs were tested, how many groups of dogs were dosed, or how high their doses ranged. In one group of dogs, for instance, the authors noted an increase in heart rate that lasted “less than three (3) hours.” Reading it, I couldn’t keep up with my own questions. How fast? How frequent? Why was it important to note that the dogs’ heart rate beat fast for less than three hours? Why not up to three hours? The wording, bizarre and full of unintentional irony, reminded me of Hemingway’s famous six-word story: Lab dogs for sale. Less than three (3).

I thought of the last protein study I screened for—that drug aimed to treat muscular dystrophy—which not only had the potential to interfere with the body’s ability to produce red blood cells, but also required two biopsies: tiny chunks of muscle taken out of the leg, an operation that might impede with the body’s ability to walk normally, they weren’t sure. This class of drugs, which bonded to the proteins of red blood cells, was fighting important diseases, but—it seemed to me—at the cost of the lab rats who tested them.

There were six base groups in the protein study, dosed in increments that made no logical sense to me, along with two “optional” groups—in case the sad humans in Group 6 didn’t decease on the spot. It was terrifying to imagine what lay beyond Group 6, which surpassed what even the study sponsors had calculated was the highest humans could take:

Group 1 100 mg

Group 2 300 mg (planned)

Group 3 600 mg (planned)

Group 4 1200 mg (planned)

Group 5 2400 mg (planned)

Group 6 3200 mg (planned)

Group 7 (optional) To be determined

Group 8 (optional) To be determined

But of course they couldn’t know. They could only guess.

Panting. Increased salivation. Vomiting. Repeated attempts to vomit. These side effects were common among another group of dogs tested, while just one dog in the group experienced “brief, generalized tremors.” In another group, there was a problem with the heart’s electrical system in an unquantified number of dogs. The unquantified dose of the study drug made the heart have a harder time recharging between beats—the technical term it mentioned was “increased QT intervals”—adding

these changes in the heart’s electrical system may lead to a condition where the heart beats with an abnormal rhythm, which can be associated with increased risk of sudden death.

At the “highest dose” tested in dogs—again no listed dose, again no count of dogs—the side effects were so interferant with normal life that the study dogs were euthanized six days earlier than planned. The part that got to me was that the dogs were always going to be euthanized. These ones were just euthanized earlier than scheduled.

I read somewhere that lab outfits rescued pound dogs from euthanization to participate in science. I imagined myself in their place. The discomfort made my heart beat faster, and for a moment I shuddered, thinking about alternatives from the incorrect-seeming rescue or adopt. Steal came to mind, but that didn’t seem right. Elsewhere, I read that some lab workers cried when their dog subjects were euthanized from how close of a bond they had formed during research; how, when labs shut down, many workers adopted their subjects. There was a way to look at the dogs as being given a lifeline, however brief, an extension, but that didn’t seem right, either. Still, there was something that the dogs got from being in the lab—something amorphous and fraught, something difficult to put into words—and it was that thing that I related to most.

ECG SCAN # 2

What if I told you there was no heart. What if the heart of the matter was my fingers held in the air counting the seconds between breaths wondering what a murmur sounds like under a stethoscope hearing that it sounds like an airplane tarmac and wanting that much distance from my body from measuring the blood as it flows into the heart from pumping like crashing waves from bad timing from cymbals from snail-heart from push from a lungful from gasp from shock of cold water from smack my face from fry my brain like scrambled eggs from cracked yolk on the table from oozing from heartbeats from prayer from hand

on chest from sweaty brow from heavy mouth from blue from sensation from

Grim from tear.

The ECG machine, invented by the Dutch physiologist Willem Einthoven, was first called a string galvanometer. Einthoven’s prototype, completed in 1902, weighed around six hundred pounds. The device looked like a mad Victorian scientist’s crafting table: set up like a desk, all gadgets and widgets and steel, topped with an instrument like an antiquated sewing machine, from which a needle, dipped in ink, beat against the steel plate like a drum.

I am imagining now. The inaugural readings, which required five people to operate, were transmitted over telephone lines from the local hospital to Einthoven’s lab at Leiden University so that the clunky machine didn’t have to be moved. The EKG was what Einthoven called it, from the German Kardio. Elektrokardiogramm: that which draws the waves of your heart like a conductor’s wand.

A nurse took my vitals then ushered me to a room to get my ECG. Another arrived a couple of minutes later, asked me to lift my shirt.

“Yeah, we’re gonna have to shave you,” that nurse said.

“Um,” I said. “No one ever had to do that before.”

“Sorry,” she said. “I don’t want to do it either.”

I lay in the medical bed while the nurse shaved a half-dollar sized coin in the middle of my chest then placed an ECG tab inside. She attached the rest of the tabs then left the small, curtained room, and me.

I had never really thought about test dogs before, but now I wondered things: how high their kennels were stacked; if they were divided by dose, or sex, or something else. I wondered where the test dogs lived and were studied; I wondered what to think of them at all. Circumventing the obvious—my own measly attempt at self-preservation—I instead thought about what devices were used to read their heartbeats, like if they were hooked up to Holter monitors, which I’d seen others carrying around in studies (an on-the-go heart reader, shaped like the amalgamation of all 90s tech gadgets) and which worked around the clock. Then I wondered how their heartbeats sounded on the other end of the machine. I imagined a heartbeat going fast, loud, faster yet, until it reached a cacophonous symphony, imagined a conductor on the other end. This is what pacemakers were: machines manipulating the heart. And then I trailed off, backtracked. Thought of heartbeats at the center of a smokey dance floor. Techno music playing from the wall speakers. Dancers fixed or fixated on the music—bodies outside of themselves. One pulse, one beat, one breath. A conductor, machine, human, who decided how fast and how slow. Beat. Slow, then; slower, until each thunderous pulse reverberated around the room. Beat. Slower yet, until one by one, the dancers littered the floor like beached fish.

The first nurse returned after my six-minute supine to run the scan. She stood there for a time, investigating the chart.

“Something wrong?” I asked.

“Give me a minute,” she said and left the room.

She returned with the other nurse and they peered at the chart together.

“It’s just arrhythmia. It means it beats at a different rhythm,” the first said.

The other pointed to a different spot on the chart.

“Bradycardia. It means the heart beats less than 60 beats per minute. But he’s still in range.”

“At 44?”

“Range is 40 to a hundred,” the other said.

I got my first ECG scan at my first clinical trial screening. I remembered the curtained area of a large lab room which I would see many times after, the ruffling and silhouettes of others in their portioned-off areas. It was there where I learned, with dual satisfaction and dread, that what I’d long worried was true: that my heart beat on the border of well and unwell.

“Your heart rate is a little under” is how the nurse put it. I was supine on the medical bed, my shirt up to my sternum, and everything was cold: the ECG tabs; the cords, which tangled around my front; and the bed itself, made only more tolerable by the medical exam paper. The nurse had hooked me up to a blood pressure cuff, an oximeter, a thermometer, and winced.

“We’ll go one more time. Try not to move,” she said. “I’ll be back in five.”

I willed my heart to pump faster, and not for the first time, eyeing the numbers on the vitals machine. 40 beats per minute was the threshold. As I felt the anxiety rush through me, I watched the numbers rise: first 38, then 41, 43, 45.

The nurse returned and hit a button. The machine popped out a piece of graph paper which she studied for a moment, then attached to my folder.

“You can take them off now or wait until later, whatever,” she said with a shrug, looking past the door to the hallway, where a row of people awaited. As I gestured to remove the tabs, the nurse left the room, ambivalent to what I did next.

“Am I good?” I asked.

“Next is blood,” she said without looking back.

On the drive home, I touched my chest from under my shirt, feeling the bristle between the electrodes and my skin. I had kept the tabs on, after all, because I liked how they felt on me. It was alien how the ECG tabs clung to me, pulling at my errant hairs, and that’s what made it thrilling; how the ECG machine sounded when it printed out the rhythm of my heart; how the names of the investigational medicines echoed when said aloud: AE051-U-11-001, PHYT-T5-PLFD/FS-1, CE-194, DS-3801B.

At home, I took selfies. Posed in my bed, sunlight straining through the closed blinds. Shirt off, covered in tabs, I felt desire. The next morning, in the shower, the hot water turned the adhesive into wheat paste. The tabs bonded to my skin, which had reddened and swelled. One by one, I tore them off as the water ran over me, each like a little pincer. The tabs left patchy hair and residue. I took pictures of the red marks on my skin.

Some heart murmurs are so loud, they’re audible to others. Mine wasn’t, but it was loud enough to take up physical space. As a tween, this space was often at my mom’s bedside, where I’d come to wake her, asking her to reassure me that I wasn’t dying. Later, it was trips to the doctor and seats on the bleachers during P.E.; it was shallow breaths and hands grabbing heart. My murmur was both a condition and a neurosis: arrhythmia and panic. A wellspring for what I couldn’t control.

It was Sufjan Stevens they were listening to as Chelsea left this plane—at least that’s what I heard. I was eighteen. Somebody said that it was the orchestral “Chicago,” but I was too scared to confirm, too scared to ask her inner circle anything, to even speak to them beyond offering strained condolences, my eyes glued to the ground. I was even too scared to ask anyone questions about the accident, like if Chelsea’d had a chance of receiving a transplant or if she died on impact, hoping the correct answer would show up on Chelsea’s very last LiveJournal post, which started, simply, “today i had a panic attack,” to tell me why it was so unfair. She was just sixteen. Her car swerved off the road and down a hill while the sun was still out.

Our extended friend group divided into who knew and who didn’t know, and I was in the latter. My job, as I saw it, was to be strong for the former. Too ashamed to grieve in public, I saved my grieving, as it were, for the internet. I pored over Chelsea’s LiveJournal after her death, reading and rereading the same couple of posts. I felt protective over her LiveJournal profile and harangued those that dared use her page for anything other than, “I miss you.” This was my way of finding closeness, and I hoped that, somewhere on the other side, Chelsea would see the act and appreciate it, knowing that I cared.

The time passed unkindly. I started to count my breaths. And suddenly, I couldn’t breathe on my own without counting. The sensation felt like a virus spreading through my body, a transformation that I couldn’t stop. I took drugs until it shut up. Dreaded sobriety. Feared it more, until I became single-minded, wanting to rip out my own heart and replace it with one that worked. Until I wanted to tear out my brain, which I decided was actually the culprit. In quiet moments, sometimes, I fantasized about being struck by lightning. In my fantasy, I was sure that the electricity would rewire my brain.

I didn’t know how to deal with these feelings either, too embarrassed to vocalize the ridiculous problem—even to my closest friends—that I had lost control of my own heartbeat, so I returned to LiveJournal to vent my suffering in private posts in the latest hours of the night, creating a persona out of my tortured state, like a character in a Goethe novel, writing by candlelight: And so much has been done to return to before, I wrote. So much work has been done. And one must wonder, to a certain extent, if one enjoys, or, perhaps, even prefers this imbalanced state. But that cannot be the case, for so much energy has been expended eradicating this enemy of self, this invader. And to even imagine that he could be invited in, as if through some back door, subterranean, is an unacceptable and untenable premise.

Still supine, I listened to the nurses debate over my heart. I was on the proverbial edge of my seat. I was taking control of my health.

In came the nurse practitioner, who studied my ECG form.

“Any heart issues?” she asked me, glancing at my file. “Heart attack? Stroke? Valve blockage? Heart murmur?”

“No,” I said. “And no.”

I lied through the questionnaire like I always did, but new doubts infected my rehearsed answers, so much that, this time, I wondered if I was believable at all.

“How does it look?” I asked, as her eyes met the ECG scan.

It’s not just that I needed the money, even though I really needed it. I lied because if there was something, I needed to hear it from them.

“It looks good. You have a low heart rate,” she said patronizingly, stretching out the word’s syllables. “It’s called bradycardia. It means you’re young and healthy. Sports?”

I nodded, both relieved and unrelieved, when she grew silent. “I’m going to check with the doctor just in case,” she said after a pause.

Once, a doctor told me that in the studies they did, the rats with tumors that ran on the wheel outlived the rats that lounged around. His spiel had something to do with why my heart rate was low, which had something to do with why study doctors asked me, without fail, if I played sports. I didn’t, but I always said I did.

“Any heart issues in your family?” the nurse practitioner asked, almost as a follow-up.

I shook my head and she stepped out.

“rSR prime has a normal QRS,” said the study doctor, bored, in the other room.

In a small room by reception, I waited for my physical—the last procedure. Two hopefuls sat across the glass wall, one symbolic step closer to approval. But even they were worlds away from it: first, labs had to come back clean; then the hopefuls had to come back and pass a screening all over again at check-in, and this was if the study wasn’t canceled, postponed, or full. As I observed the pair of women, a nurse scurried by, stopping the one on the right as she was called up by the receptionist.

“Hi there,” I heard the nurse say as the door swung closed behind her. “So we were taking a look at your ECG. . .”

I couldn’t hear what the nurse said next, but the context was clear enough. The nurse was now speaking with the receptionist. She gestured back to the hopeful, who stood up, visibly dejected, and collected her things. For a moment, we shared brief, intense eye contact. I tried to tell her sorry with my eyes, sorry for staring and for her dismissal, but I wasn’t sure that’s what was communicated on my face. What I was feeling was pure ambivalence: both utter relief at being chosen and a kind of jealousy at her knowing.

For I was convinced that the doctors had missed something: they had, in fact, not detected my murmur. In a hundred checkups, only two study doctors had noticed it. That, or at least just two had decided to point it out to me—but I leaned on the former, the story I wished to believe. Still, I was sure of one thing: that if I told the doctors about my murmur, my fate would be the same as the woman beyond the glass window. Gone; booted for my raised risk, and unlikely to be invited back. And what would I do then, so chronically dependent on the testing lab to deliver me a bill of health?

ECG SCAN # 3

What if I told you I never looked back. What if I told you I took the chart with me ink spreading over the telemetry paper like jet-black jam the story of the heart on a single page. What if this was not about texture, but touch the pressing of 10 tentacles against my chest in search of the angle of Louis the smushing, my wellness check like ripe berries for the press my first position my sternum—bony & the little jumper cables clamped to the tab’s nipples passing electricity like lightning like morse code my V2, to the left of the sternum, my V4 my rotation my hyperbaric chamber my V3, just in between my V5, my axilla my chest fat, sticky with residue my V6 my armpit my money shot. What if I told you I was practicing preparedness was ready for any machine to read me for health was satisfied. What if I lied to myself said you are healthy what if it was true what if I took pictures pursed my lips like Justin Bieber said all I need is a beauty and a beat what if I came from an infamous psychiatric hospital what if I escaped with my electrodes my protective crystals my jailbreak.

A Dream

My dream is full of childhood references. Bright colors flood a scene out of the Babar picture books: a place where elephants, tigers, and lions could walk on two feet. All of the color in the world is stored in that place, enveloped by blank space. If there’s a world outside, it’s odorless and unformed, a starry-grey nothingness. A plush red heart travels across a room, part bedroom and part lab, past bunks stacked three-high, vitals machines, and teenage wall art. A crocheted computer sits on a desk, a Livejournal post types on the screen. In my dream, I reach for my heart, realizing, with comic exasperation, that it has burst out of my chest, that my hands are yarn. I follow the threads of red yarn that attach me to my heart. I follow the threads, and the world becomes vaporwave, like a Windows 95 screensaver, another reference point to measure my heart, which is breaking out of me. My heart is hooked to a pixelated ECG machine. It is sliding out of an open door into the liquid-grey void, to Chelsea. As it pitter patters through the electric air, I log its movements with the tap-tap of the keyboard, postulating just how far it might go this time. To Be Determined. I observe the evolving scene, calculating the measurements between reference points, between electrodes and deep breaths, between machines and memories, between myself and my heart.

I am in a heightened state. My lightning.

Tell us your origin story as a writer. When did you begin? What first drew you to writing as an instrument for asking questions that can’t be explored any other way?

C.R. CALABRIA: I grew up absorbing my mom’s stories. My mom is one of the most fantastic storytellers I’ve ever met. Everything you’d want in a tale is in her stories, and she so effortlessly modifies them for her audience—introducing context, characters, each with a detail that if you know them you’d think, That’s exactly how so-and-so is. We moved every couple of years growing up because my dad was in the military. As my outside world was ever-changing, my mom’s stories were my constant—an anchor to the shifting world around me, but also an orientation, a compass that guided me to what and where I was, one that I would later, in part, reject, but that was foundational to me. That’s what got me into stories, but I never got my mom’s gift of gab.

I remember in elementary school being sent to a speech therapist during class. I stuttered and had vocal tics—what I would much later identify with words like dyspraxia or language processing disorder. In those years, after school, my brother and I would sit in the common areas outside of my mom’s college while she was in class, two bored kids with markers and color paper. My first many books were written there, and they were all collabs with my brother, full of maps and character drawings and tales from the same multi-planet galaxy we created. These were expressions of elsewhere: outsiders looking in. And we were indeed always elsewhere.

What does your writing routine look like? Do you thrive in structure or wildness? And when you begin a piece of writing, what tends to announce itself first: a voice, an image, an unease, a philosophical conundrum?

CRC: Structure is important to me, but I’ve never successfully implemented a writing structure longterm. I need variety. One month I’ll try to write x number of minutes/hours per day, another month I’ll follow daily writing to-do lists, another I won’t write anything at all. I really can’t make myself do something I don’t want to do, so writing becomes a regular habit of tending to the soil of my motivations and aspirations, too.

New pieces announce themselves in a fury, often when I’m walking or driving, and then I find myself dictating into my phone, or late in the night, when I'm between awake and asleep. I’m not very imagistic, and what often presents itself is striking associations between disparate things.

Most of my new pieces actually come from productive procrastination, which I have found to be one of my most productive writing strategies, and the reason why I always have multiple writing projects going at once. Productive procrastination allows me to manufacture some amount of autonomy, I guess.

Most artists are preoccupied by certain obsessions: lust, longing, death, the self. What persistent preoccupation—emotional, intellectual, or spiritual—threads through your work? Are there motifs, themes, or impulses you’ve tried to abandon but that keep returning, insisting on their relevance?

CRC: Whether I like it or not (and I often don’t) my writing is a lot about belonging. I consider military brats to be third-culture kids, and like many third-culture kids, I’m preoccupied by the idea of translation, or how you tell the story of one group of people to a different group of people with different reference points. I’m also preoccupied by the body, especially the limits of our current understandings of consent when it comes to embodied labor in capitalism.

If not a writer, who would you be?

CRC: This is a funny question. You know, I didn’t even identify as being a writer until recently, and now I love to use it to describe myself, and to identify and process the shame that comes with it—the feeling of self-aggrandizing or being “too big for my britches,” to use the Southern term. Our country is so anti-intellectual and I was raised so anti-intellectual that I tend to project these judgments outwards. That being said, I used to think of “writer” as more of an action, and that’s how I tend to think of any occupation, as something that you’re either doing or not doing. I have a lot of those in my arsenal at any given time, and they rotate. But where writing goes, at some point that changed—I crossed over—and now “writer” is an ingrained part of my identity, much like “smoker,” whether or not I’m smoking at any given time.

There’s still an activeness in the word writer for me, but now it’s more related to time and distance. I think a lot about pilgrimages in general, and that’s sort of how I conceive of the journey (sorry) of self-identifying as a writer. You travel far enough that eventually when you look around, the terrain is different.

What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received? Alternatively/additionally, what’s something you’d like to offer as advice to emerging writers trying to make a mark?

CRC: I find myself suspicious of writing advice, but a good, timeless piece of advice I've received is to always be reading. I find that reading is especially useful when I have a writing project I’d like to begin or pick back up. I read, I get inspired, and then writing becomes easier.

I’m not sure that I’m in any place to give writing advice, and I still identify as an emerging writer. That said, something I see affecting a lot of fellow emerging writers is a rush to get bylines. You don’t need to be publishing all the time. If it makes you feel good, that’s great, but it doesn’t make you any more of a writer. Good stories take time, and the timeline that a lot of good writing requires is so different and antithetical to our culture of instant gratification. Like, if you think something is done, put it down for a month, read something inspiring, then pick it back up, and then if you still think it’s done, send it out. Or find a trusted reader. I sent this piece to a trusted reader––my boyfriend, who is a fellow writer––and with the notes I got it transformed into a much better essay. Not perfect, but better.

The elite writing world, the one that many emerging writers dream of being apart of, is privileged and nepotistic, just like everywhere else. There's a lot counting against you if you didn't go to a fancy school or don't already have those built-in connections. Like, I hate that I don't have an editor friend that I can call in a favor to get my story out of the slush, or pass my pitch along to someone who would read it like it came from that of a friend of a friend, not a stranger. You can't change that. However, the more you participate in the literary community that you want to belong to, the more you make connections, and the more connections you make, the more you are vetted, and in the literary world vetting does matter, as much as people pretend like it doesn't.

What are you working on now and how is it trying to ruin your life (in a good, necessary way, of course)?

CRC: I am writing my debut book of nonfiction. It’s called Lab Rat, and it tells the story of our relationship to drugs through the people and animals who test them, and who have tested them throughout history. This is a project that started about four years ago, and a lot of the preliminary work has been to figure out how to write a book as much as what kind of book I want it to be. Lab Rat is anchored by my personal experiences––I have been a Phase I human research subject since 2011––but the book I want to write is much bigger. It's more of an anti-history, mixed with what I hope to be deep contemplations about drugs and healing. Like, what if the human research subjects throughout history were to tell you the story of medicine? How would they––we––tell it different? Medicine is wonderful, but I think that the story that the medical establishment likes to tell about itself tends to bury or obscure the murky parts, and those are the parts I'm interested in because they often involve us. And I mean all of us—we all take drugs.

For the longest time I was just a nosy human research subject. When I'm in a study, I ask a billion questions. So once I started taking writing more seriously, I had a lot I'd already been marinating on. This coincided with talking to people outside of my bubble about clinical trials, which I hadn't really done before. What I found was that most people had no idea what I was talking about, had never even heard clinical trials, even though every single pharmaceutical drug they will ever take first goes through them. That's the heart of my book, I think—giving humanity to the human research subject, who has been essential to every medical advancement since the Age of Enlightenment, but who is really a discarded figure.

Who are the artists—writers, filmmakers, thinkers, internet oddities—that have shaped your sense of narrative? How have they rearranged the way you see the world on the page?

CRC: I consider Samuel Delany to be one of my biggest influences, and it’s not just because I love his work. Early on, I heard that Delany was dyslexic, and as someone who has a learning disability, I really stuck to that. Knowing that he made a literary career work for him, that someone went behind him and corrected all of the errors in his manuscript, that helped him make his manuscript more legible for a wider audience while preserving a quality that I think is neurodiverse, that helped me feel like there was space for me.

Neurodivergence is essential to how I view narrative, because narrative for me is a constant negotiation. A story reads one way to me and another way to readers. This is a normal thing all writers deal with, but it took me being in an immersive writing program to realize how much wider the comprehension gulf is, how every story I write is essentially about negotiating the grey areas between difference and craft. This is all something I’m in the nascent stages of grasping, and I’ve been inspired by the work of early disability activists like Ellen Samuel, Robert McRuer, Alison Kafer, by concepts like “queer time” and “crip time,” and by people like Elaine Glaser, who recently wrote a great article for Aeon about the limits of narrative.

Please recommend a piece of art (a painting, a film, an album, anything that's not a piece of creative writing, really) that you love and would like everyone to experience.

CRC: I was talking this question over with my longtime best friend and she jokingly mentioned Ryan Trecartin's films, specifically 2007's I-Be Area. This extremely experimental, basically randomcore film was an important watch for me and my friends at a young age, but nearly 20 years after its release, the microbudget art film has revealed itself as much more prescient than I could have imagined. Like, back then, that kind of hyper-onlineness, where the digital world was almost a literal extension of the self, like an appendage, was niche. But in 2025, the entire world is chronically online. So the kind of endless scroll brain rot hyperpop mush that is central to Trecartin's films is now central to modern life, a life in which we can’t describe or even see ourselves without the filters of the internet. But that's not to say that his films are shallow, I think they're quite deep.

I recently saw Center Jenny, a film of his which came out in 2013, and I liked it even more. There's something that Trecartin does that taps into deep consciousness, like a source code for gay people. There's a lot of heavy hitters in there, too: Alia Shawkat, Aubrey Plaza, and Jena Malone, among others. I have no idea how they all got involved, and with the exception of Plaza, you can barely tell it's them with how Trecartin distorts the frame.

C.R. CALABRIA is a writer and lab rat. A finalist for the 2025 Ninth Letter Literary Awards, Cory’s work appears in Brevity and Pit Magazine, and he’s working on a book about human research subjects. He lives in New Orleans, Louisiana.

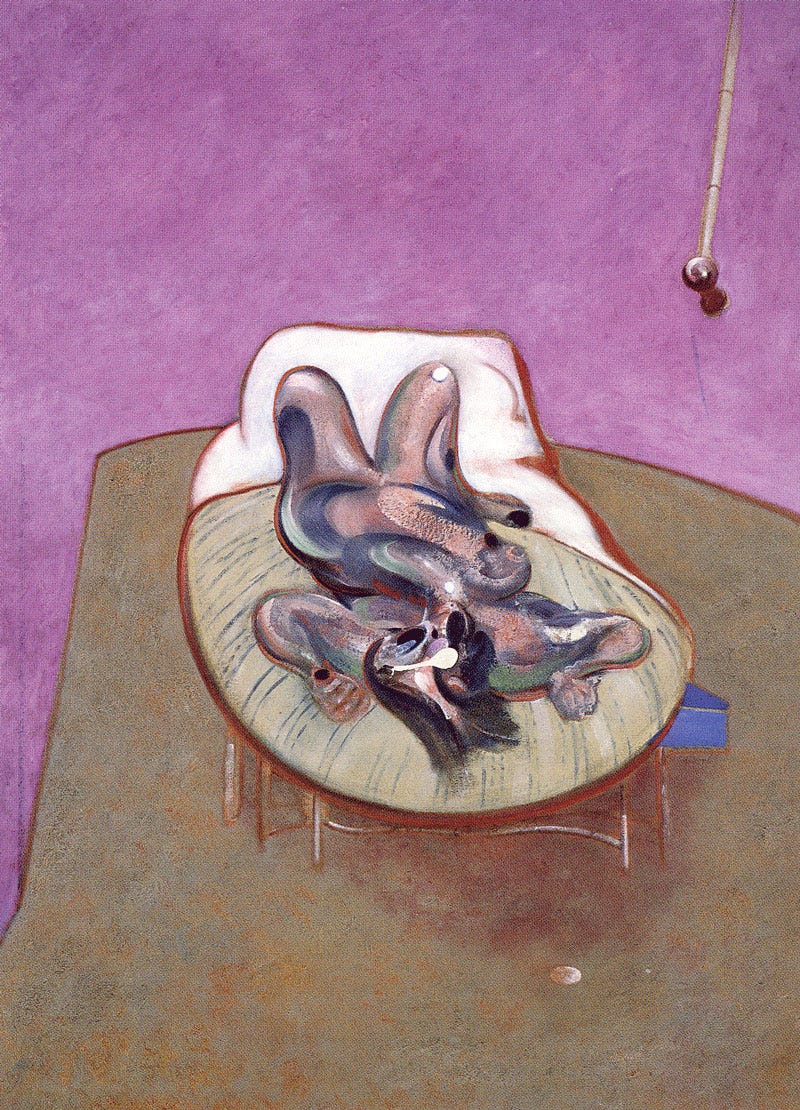

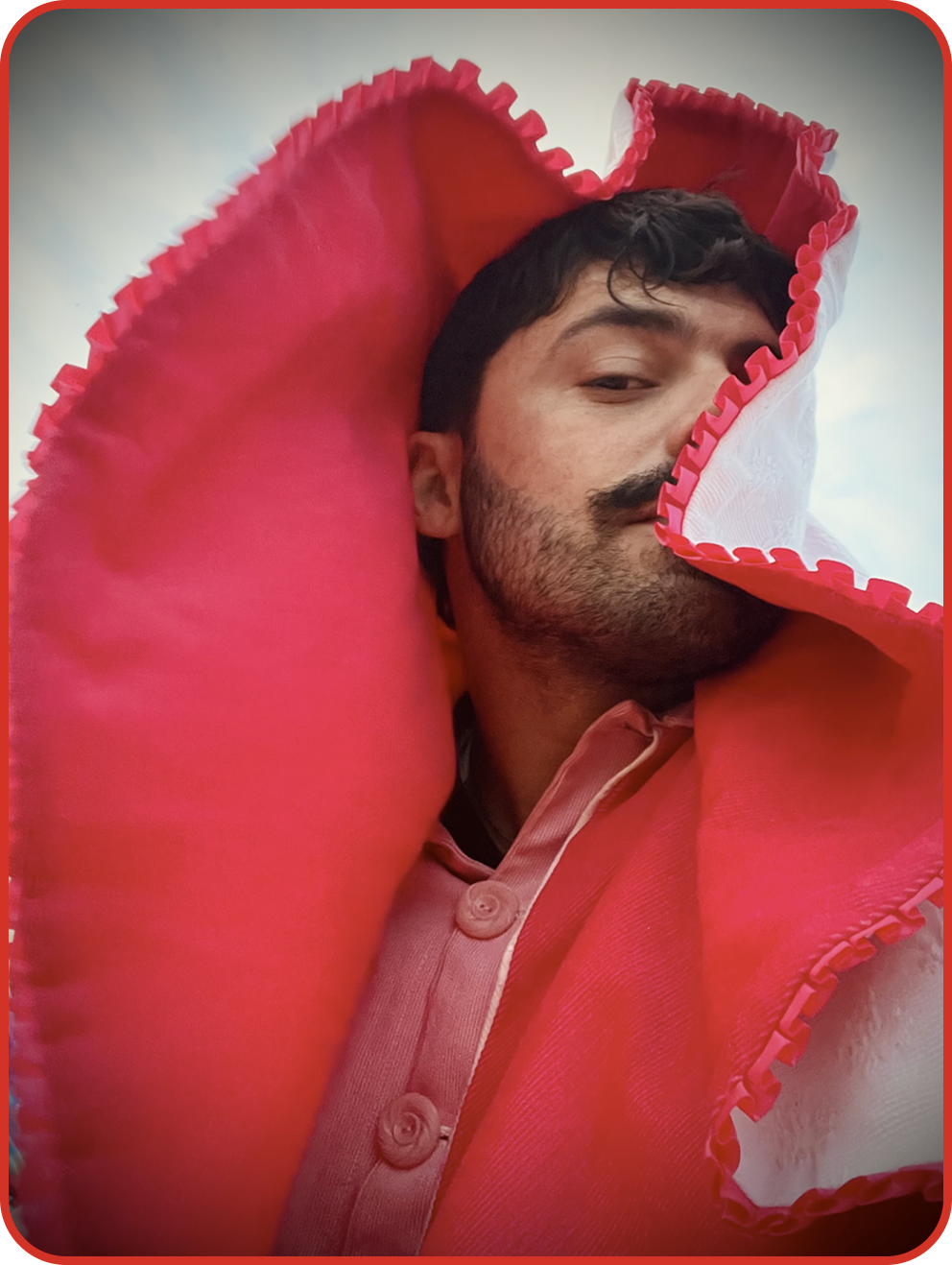

Note on Art

We’ve paired this piece with Francis Bacon’s Lying Figure (1969)1. Bacon painted bodies on beds—medical beds, hotel beds, beds that become stages for observation. His figures melt into the surfaces meant to hold them. The bed becomes a petri dish, the body becomes specimen. There’s something strangely, brilliantly erotic in it, and also something deeply alone. Calabria’s essay lives in that same room.

Image: Lying Figure (1969) © Francis Bacon. Used for editorial commentary purposes only. All rights reserved.

The way the ECG turns measurement into intimacy—almost desire—felt central here. I’m curious whether you see this as reclaiming the body from medical abstraction, or as exposing how deeply we’ve internalized being read by machines.

that was a beautifully written extract out of his new book. i especially loved the interview questions and him musing about being neurodivergent :)