7 Short Lessons from Gabriel García Márquez

Learn from a rare & timeless conversation between friends | + 7 Writing Exercises

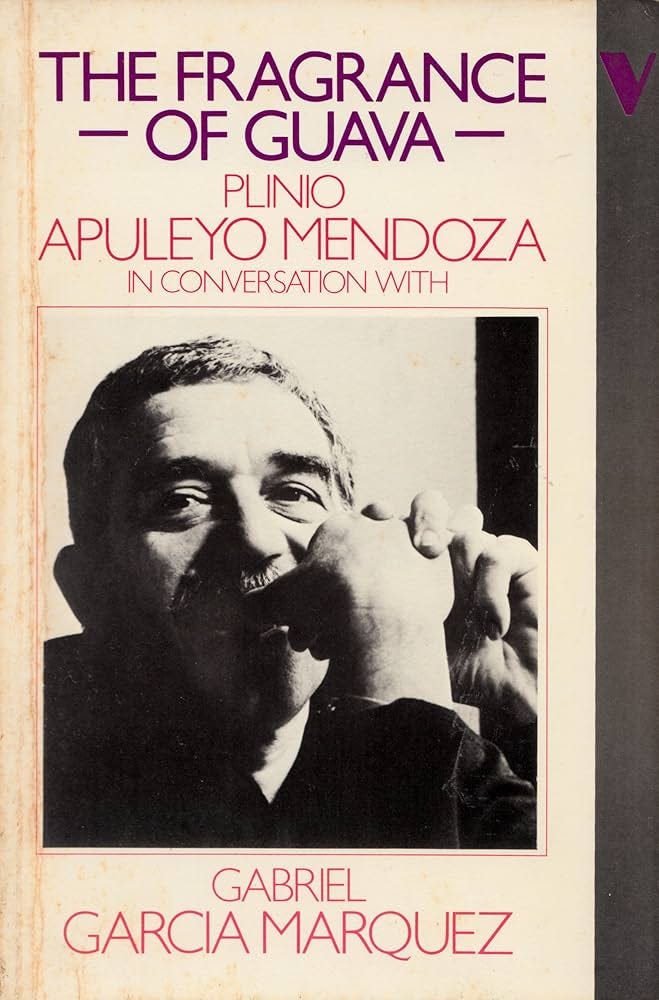

One of the best books we read last year was THE FRAGRANCE OF GUAVA, a conversation between friends: journalist Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza and Nobel-Award-winning novelist Gabriel García Márquez. The book’s surprisingly not so widely read or even known from what I’ve gathered, but I’m so grateful to the bookworm gods for allowing me to chance upon this beauty in a used bookshop.

Now, before I dive into our 7 timeless Márquezian lessons, I’ll recommend to each and every one of you to please buy yourself a copy yesterday.

Paired with these, we have 7 Writing Exercises “Stolen” from the Master himself, complete with detail, examples, and direct quotes from Marquez. Though the lessons below are all free to read, the exercises are accessible to our paying subscribers only. Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to support our work and efforts here at Strange Piglrims towards indie lit.

Write Like Márquez: 7 Exercises "Stolen" From the Master"

Everything below comes directly from how Gabriel García Márquez actually worked. Each exercise takes a principle from the book and turns it into something you can do this week to practically improve your writing or enter deeper into work you’re already wrestling with.

1. Imagination and fantasy are opposites

This is probably one of the most important thing Márquez ever said about making things, and almost nobody quotes it.

“Fantasy, in the sense of pure and simple Walt-Disney-style invention without any basis in reality, is the most loathsome thing of all.”

Every so-called supernatural event in his fiction traces back to something that actually happened. The yellow butterflies that follow Mauricio Babilonia in One Hundred Years of Solitude? When Márquez was five, an electrician kept coming to change the meter at his grandparents’ house. His grandmother tried to shoo away a butterfly with a duster, saying, “Whenever this man comes to the house, that yellow butterfly follows him.” This was the seed for Babilonia.

Remedios the Beauty ascending to heaven? A woman in town whose granddaughter had run away in the early hours of the morning “tried to hide the fact by putting the word around that she had gone up to heaven.” Here, Márquez describes how he wrote the actual passage:

Yes, she just wasn’t getting off the ground. I was frantic because there was no way of making her take off. One day as I was thinking about this problem I went out into my garden. It was very windy. A very big, very beautiful black woman had just done the washing and was trying to hang the sheets out on the line. She couldn’t, the wind kept blowing them away. I had a brainwave. ‘That’s it ,’ I thought. Remedios the Beautiful needed sheets to ascend to heaven . In this case, the sheets were the element of reality. When I returned to my typewriter, Remedios the Beautiful went up and up with no trouble at all. Not even God could have stopped her.

The distinction matters more now than it ever has. We live in an age of pure invention — AI-generated images, endless fantasy world-building, content conjured from nothing. Márquez would have found all of it loathsome (yes, we’ll bet on it). Not because it’s technology, but because it’s disconnected from the lived world. The difference between imagination and fantasy “is the same as between a human being and a ventriloquist’s dummy.” (Sorry to break it all us hardcore fantasy lovers haha).

2. You only write one book your whole life.

Márquez believed every writer spends an entire career circling one obsession. Balzac did it. Kafka did it. Faulkner did it. His was solitude.

The Colonel waiting Friday after Friday for a pension that never comes. Aureliano Buendía waging 32 wars and ending up alone making little gold fishes. The Patriarch so isolated by power he’s no longer sure of his own name.

When Mendoza asks where this obsession came from, Márquez says, “I think it’s a problem everybody has. Everyone has his own way and means of expressing it.”

Then he offers the key to the entire Buendía family, maybe the most revealing single sentence he ever said about his most famous book: “The Buendías were incapable of loving and this is the key to their solitude and their frustration. Solitude, I believe, is the opposite of solidarity.”

3. A good idea can wait decades. If it can’t, it wasn’t good.

Márquez held One Hundred Years of Solitude in his head (and heart) for 15 before writing it. The Autumn of the Patriarch took 17. Chronicle of a Death Foretold took 30.

30 years.

When asked if this worried him, he said: “I’ve never really been interested in any idea which can’t withstand many years of neglect.”

He never took notes. “When you take notes you end up thinking about the notes and not about the book.” He waited for the missing piece — the tone, the structure, the one detail that made the whole thing fall blissfully into place. For One Hundred Years, it was the realization that he had to tell the story the way his grandmother told hers: deadpan, mixing the extraordinary with the ordinary, never flinching. For The Autumn of the Patriarch, the missing piece came from a book about hunting in Africa. He’d been struggling with the dictator’s psychology for years. Then he read a chapter on elephant behavior, and it unlocked everything.

In an era of content calendars and bi-weekly newsletters and AI drafts generated in seconds, Márquez is a standing rebuke. The most important phase of creation looks like nothing is happening. We’re systematically destroying our capacity for it.

4. The first sentence is a laboratory.

“The first sentence can be the laboratory for testing the style, the structure and even the length of the book.”

He said it sometimes took him longer to write the first sentence than the rest of the book combined. The famous opener of One Hundred Years of Solitude (“Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.”) contains the entire novel’s method in miniature: the telescoping of time, the melding of violence and wonder, the central character, and of course the charming storytelling voice.

5. Your grandmother is a better teacher than your MFA

When Mendoza asked who had been the greatest help in his long apprenticeship as a writer, Márquez didn’t name Faulkner or Kafka or Hemingway. He said: “My grandmother, first and foremost.”

Doña Tranquilina told stories about the dead walking through the house as if she were describing what she’d had for lunch. So it’s natural that “[Marquez] wrote One Hundred Years of Solitude using [his] grandmother’s method.”

This is worth sitting with. The most celebrated novelist of the twentieth century learned his method not from literature but from an elderly woman in a hot, crumbling house in a Colombian banana town who talked to ghosts. The technique that made him world-famous — treating the impossible as mundane — came from watching her do it every day.

He did credit Kafka with helping him realize he could be a writer: “When I read Metamorphosis, at 17, I realized I could be a writer. When I saw how Gregor Samsa could wake up one morning transformed into a gigantic beetle, I said to myself, ‘I didn’t know you could do this.’” The connection went deeper. Kafka, he said, “recounted things in German the same way my grandmother used to.”

6. Reality is wilder than anything you can invent.

“There’s not a single line in my novels which is not based on reality.”

He made a larger point about Latin America that applies well beyond it: “Everyday life in Latin America proves that reality is full of the most extraordinary things.” An American explorer saw a river with boiling water in the Amazon. Winds from the South Pole swept an entire circus away in Argentina, and fishermen caught the bodies of lions and giraffes in their nets. A boy turned up in Barranquilla claiming to have a pig’s tail, after Márquez had written about one.

“I know very ordinary people who’ve read One Hundred Years of Solitude carefully and with a lot of pleasure, but with no surprise at all because, when all is said and done, I’m telling them nothing that hasn’t happened in their own lives.”

The lesson: if your work feels thin, you don’t need more imagination. You need to pay closer attention to what’s already there.

7. Protect the conditions for working. Everything else is negotiable.

Márquez was specific about what he needed: a quiet, well-heated room. 9am to 3pm . An electric typewriter and 500 sheets of paper. Yellow roses on the desk. He wore mechanic’s coveralls while writing. If the rose was missing from the vase, the words wouldn’t arrive. When he put it back, everything flowed.

He was also ruthless about what he didn’t need. He loathed television, congresses, conferences, round tables, and interviews. He stopped writing letters entirely after discovering someone had sold his correspondence to a university archive.

“I don’t hold with the romantic myth that the writer has to be starving and all screwed up before he can produce. You write better if you’ve had a good meal and you’ve got an electric typewriter.”

Mercedes, his wife, understood this completely. When he turned the car around on the highway to Acapulco because the opening of One Hundred Years of Solitude had suddenly come to him, she took charge. He pawned their car. She got the butcher to extend credit for meat, the baker for bread, the landlord to wait nine months for rent. She brought him 500 sheets of paper whenever he ran out. She never read the manuscript. When it was done, she mailed it to the publisher herself, thinking: “And what if the novel turns out to be no good after all this?”

Serious creative work requires a kind of almost maniacal logistical protection, and someone — yes, most likely you, if you don’t have as supportive a spouse as Mercedes — has to build the scaffolding around the precious hours.

We hope these lessons were as invigorating to read for you as they were to create for us. Once again, we’d recommend you read the entirety of FRAGRANCE OF GUAVA. You can also access our practical companion of all 7 related writing exercises here:

With gratitude,

Note on Art

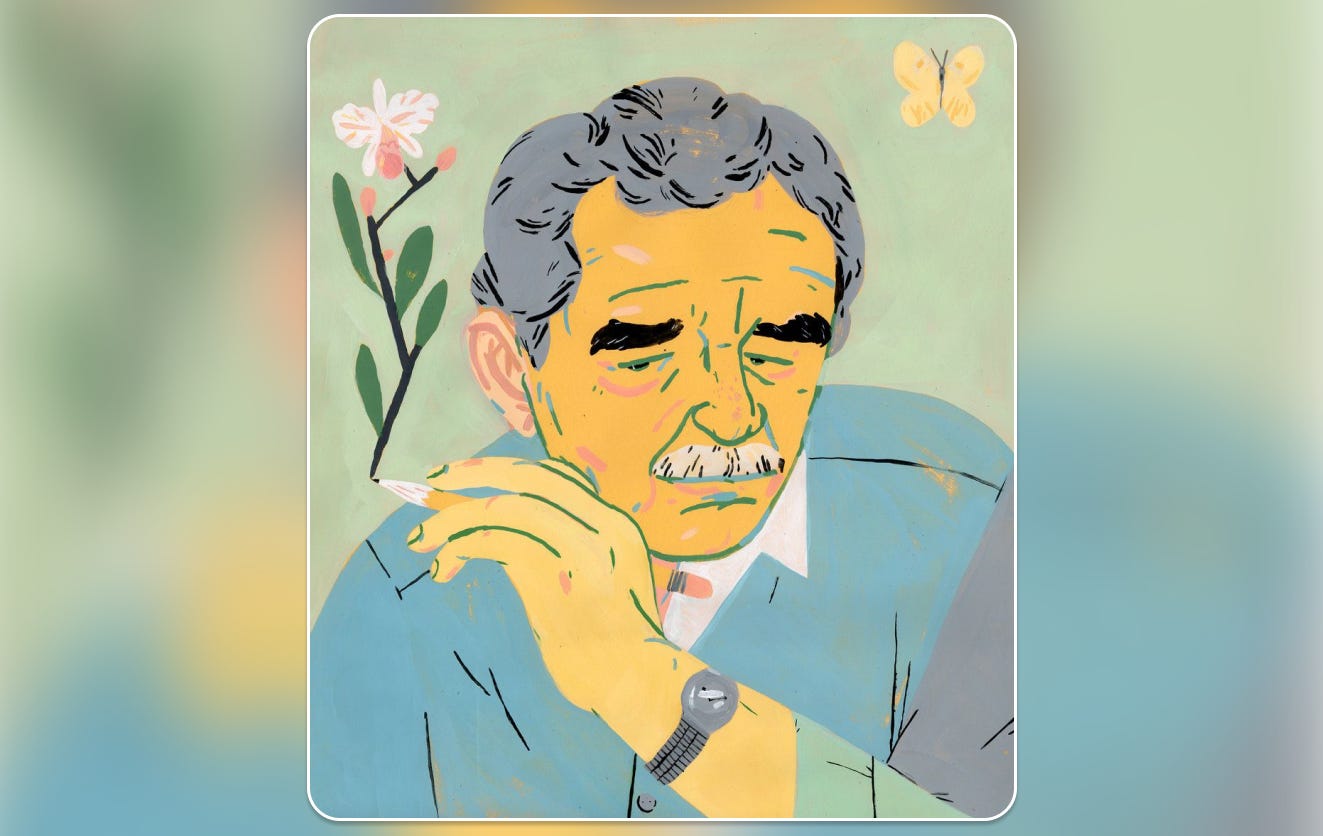

The portrait1 used above captures something Márquez said about himself: that he was more superstitious than rational, more Caribbean than literary. The yellow skin echoes his famous obsession with the color — yellow roses on his desk, yellow butterflies in his fiction — while the closed eyes suggest the inward gaze of a man who trusted his grandmother’s ghost stories more than any writing workshop.

Image: Gabriel García Márquez © Celia Jacobs. Used for editorial commentary purposes only. All rights reserved.

Beautiful, every word. Thanks.

Loved this. Maybe my favorite -" I’ve never really been interested in any idea which can’t withstand many years of neglect.” - Maybe. Thank you for the book suggestion.